While researching this article, I saw a Reddit post that made me pause. A man had asked quite sincerely, “When is it okay to compliment a woman on LinkedIn?” Predictably, the comments were divided. Some users, thankfully, reiterated that LinkedIn is a professional platform, not a dating site. But others chimed in with advice straight out of a pickup artist’s handbook: “You should approach a woman wherever you can — what if LinkedIn is your only shot?”

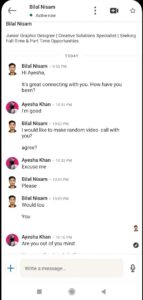

That one post encapsulates the quiet but growing problem of harassment of women on LinkedIn. Women are increasingly being treated less like professionals and more like prospects. And it’s not just one-off anecdotes; there’s data, and a lot of it.

Related: Not Just Token Feminism, This Is What Women Actually Want From Their Workplaces

The tinder-ification of LinkedIn

A 2023 survey quoted by Forbes painted a pretty grim picture: 90 per cent of women who use LinkedIn weekly reported receiving romantic or sexually inappropriate messages. Even more disturbingly, nearly a quarter of them received such messages daily or every other day.

Let that sink in. A platform meant for career growth is now a hotbed for digital sleaze and not the kind you can just block and forget. A Statista report echoed this: 30 per cent of women get inappropriate messages every month, with more than 25 per cent experiencing it daily or every other day.

Cybersecurity expert Shubham Singh points out that it’s ridiculously easy to harass women on LinkedIn. “All it takes is a fake name, stock photo, and some copied job titles. These fake profiles can: Scrape data from real users. Spread malware via links. Impersonate recruiters to phish resumes or personal info. Gain trust by joining mutual groups or connecting with real professionals.”

Is LinkedIn unsafe for women?

It’s tempting to brush off a creepy message with an eye roll and a “delete.” But over time, this casual, persistent harassment takes a toll. According to the International Journal of Public Health, non-physical forms of sexual harassment, like inappropriate messages, are linked to anxiety, depression, poor self-image, and lowered confidence. The emotional cost is real. And so is the professional one.

A whopping 74 per cent of women said they’ve reduced their LinkedIn activity as a way to protect themselves. Fewer posts, fewer connection requests accepted, and in many cases, keeping a lower profile altogether. In other words, women are having to scale back their ambition online just to stay safe.

Plus, LinkedIn’s policies regarding blocking aren’t as robust as they should be. Singh says, “LinkedIn could use more proactive measures. Let users approve who sees their profile photo or contact info. Allow anonymous browsing to be blocked. Add ‘block without visiting profile’ or more robust filtering for connection requests.”

Harassment of women on LinkedIn: It’s the culture

Scroll through Reddit and you’ll find plenty of women echoing the same experience. Indian academic and journalist Nishtha Gautam described being “utterly helpless” after what seemed like a normal connection request spiralled into a flood of inappropriate messages.

And that’s the crux of the problem. LinkedIn isn’t designed like Instagram or WhatsApp. There’s a built-in assumption of professionalism. So when a woman receives a lewd message, it feels like a double violation of personal space and professional respect.

Part of the issue is cultural. With 57 per cent of LinkedIn’s user base being male, women are already navigating a platform where they’re in the minority. To LinkedIn’s credit, they’ve introduced features like message reporting and AI moderation. But ask any woman who’s flagged a message and got the automated “this doesn’t violate our guidelines” reply, and you’ll know it’s not working fast enough, or well enough.

What can we do?

For many of us, LinkedIn is vital for career growth. But women should be cautious of certain behavioural patterns in messages and profiles. Singh highlighted the kind of profiles that are a big no:

“Profiles with few connections, generic job titles, or no mutual connections. Recruiter profiles that don’t match the company domain. People who push for personal contact info early on. Incomplete profile, lack of engagement, unprofessional content, or inconsistencies in information.”

Singh recommends several simple yet effective safety strategies:

- Limit visibility: Set your profile photo and contact info to ‘1st-degree connections only.’

- Customise connection request filters: Avoid accepting unknown requests blindly.

- Turn off visibility of your activity status.

- Use the ‘block and report’ function immediately when something feels off.

- Avoid linking personal email or phone numbers to your profile.

He also suggests using a few practical browser tools:

- PeopleLooker or Social Catfish: For reverse image searches on profile pictures.

- Malwarebytes Browser Guard: Warns about suspicious or phishing links.

- uBlock Origin: Helps filter out tracking and malicious content.

- Privacy Badger: Detects trackers and stops them from collecting your data.”

“Keeping your browser and antivirus updated and enabling two-factor authentication on your LinkedIn account are essential safety measures”, Singh says.

LinkedIn is supposed to be the internet’s boardroom. But for many women, it’s starting to feel like just another space they have to cautiously navigate. And if LinkedIn wants to preserve its credibility, it needs to treat safety and privacy not as user-end responsibilities, but as platform-level priorities.

Featured Image Source

Related: Women Donate Organs 80% More Than Men: The Gender Gap In Live Organ Donation

Web Stories

Web Stories