When Alakh Pandey, popularly known as Physics Wallah, walked into a government girls’ school near Bareilly, he expected the usual warmth of recognition. And at first glance, it seemed no different. Girls chanted his name, and teachers beamed with pride. As he asked the students to take out their phones for a selfie, one of them hesitated, “We don’t have phones,” she said. The teacher would take the photo and send it to them. Confused, Pandey asked if they didn’t own mobile phones at all. The response was heartbreaking: “We do, sir, but our parents don’t give them to us.” The reason? The teacher said, “If girls use phones, they’ll run away.” In many rural households across India, mobile phones are still seen not as tools for learning but as threats to tradition, especially when it comes to daughters. This incident tells us so much about gender inequality in education in India.

Related: Is LinkedIn Unsafe For Women Now? Cybersecurity Expert’s Online Safety Tips To Follow

A promise not yet delivered

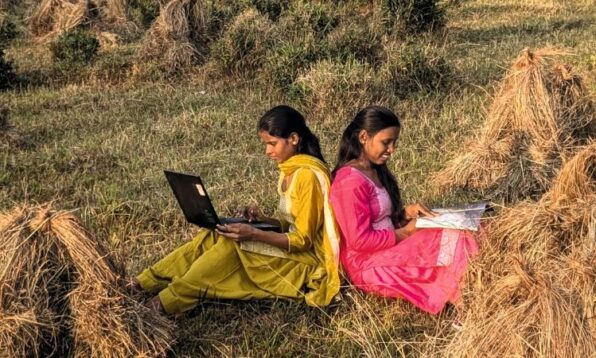

For all the buzz around Digital India and its potential to democratise education, the numbers tell a sobering story, especially for young women in rural areas. In the critical age group of 15 to 24, nearly three out of four rural boys own a mobile phone. But when it comes to girls? Barely half can say the same. And even having access doesn’t always translate to meaningful usage. In the age of online classrooms and YouTube tutors, here was a group of Class 11 and 12 girls who didn’t just lack access; they didn’t even know who he was. Not because they weren’t interested, but because they’d never been given the chance to explore. It’s a brutal reminder that while education may now be reaching smartphones, those smartphones aren’t necessarily reaching girls. There is still a huge gap to fill when it comes to gender inequality in education in India.

Statistics of girls’ education in India

On paper, India’s girls are going to school. The Gross Enrolment Ratio for girls at the primary level now exceeds 100%. However, many girls leave school around puberty due to unsafe commutes, lack of toilets, menstruation taboos, or pressure to help with household chores.

More worryingly, the advent of digital learning has created a new kind of exclusion. While boys in many households are encouraged to use mobile phones to study, girls are denied the same opportunity. The fear isn’t just about distractions or screen time; it’s about morality, mobility, and control.

The Beti Bachao Beti Padhao paradox

Launched in 2015 with a powerful rallying cry, the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP) scheme was hailed as a landmark step for gender justice. And to be fair, it has delivered progress. The child sex ratio has improved in many districts, especially where focused campaigns were run. In Haryana’s Karnal, for instance, it jumped from 758 girls per 1,000 boys to nearly 900. More girls are being born, more are entering schools, and many are excelling.

But the picture isn’t uniform. For every district that improved, there are others where the needle hasn’t moved or has worsened. A significant chunk of BBBP’s funds, almost 80%, has gone towards publicity campaigns rather than actual grassroots interventions.

In some ways, the scheme has become a slogan without substance for those who need it most. And that’s where Pandey’s anecdote hits hardest. These girls were being posed in front of a camera, not out of pride, but to benefit the school’s name.

The cultural hurdle

What makes this issue so sticky is that it’s not just about money or infrastructure; it’s about mindset. The fear that education or exposure might lead girls astray is a persistent one in parts of rural India. Parents worry that letting daughters use phones might lead to relationships, rebellion, or even running away from home. This fear is often wrapped in the language of protection, but its effect is suffocating.

India cannot afford for its digital revolution to leave its daughters behind. If the pandemic taught us anything, it’s that access to technology is no longer a luxury in education; it’s the lifeline.

Alakh Pandey’s story isn’t just an anecdote; it’s a mirror. A mirror that reflects the uncomfortable truth that while we may have slogans like Beti Padhao, we haven’t truly created a world where girls are free to learn.

To know more about Alakh Pandey’s insights on education, watch the full episode here.

Featured Image Source

Related: Ladies, It Is Either Education Or A Happy Marriage. Pick Your Poison

Web Stories

Web Stories